Naomi here. We’ve talked quite a bit this month about taxes and money, both current and Regency related. But one thing we haven’t looked at was how the people of Regency England felt about those taxes, and even more importantly, how the people thwarted those taxes.

Isn’t it rather interesting to know that people have been evading taxes for hundreds of years? The concept is hardly new, though the methods and means have changed through the centuries.

So, now you’re asking, how did the English population avoid all those hefty taxes? Well, not all of them could be avoided (here’s a little list of some of the more odd Regency taxes). But duties or import taxes could be easily avoided through:

Smuggling.

That’s right. Smuggling, that dastardly century-old business. England being an island and therefore surrounded by water, imported and exported all its taxable goods via shipping. There are lots of places along the English coast where sailing vessels could harbor and unload their goods away from the watchful eye of the revenue agents.

Anything that was taxed–which was pretty close to every purchasable good imaginable. Tea and brandy were two of the biggest items, but that list would also include salt, leather, soap, chocolate, fabric, and cigars.

Furthermore, during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars, French imports were banned from England. And France made things craved by the British upper class, like silk from Lyons and lace from cities such as Alencon and Arras and Dieppe and Le Puy.

And of course brandy.

If there’s one constant in smuggling throughout the annals of history, it’s this: smugglers always deal with spirits.

Where were the goods smuggled?

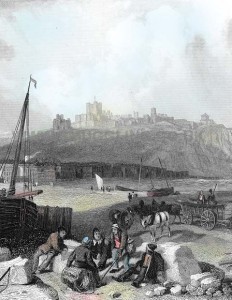

Though the whole of the English coast was subject to smuggling, smuggling occurred in greatest concentration along the English Channel. A quick little jaunt to France and back allowed for smuggling en masse in this region. The County of Kent, which lies nearest France and at it’s easternmost point is separated only by a few miles of water, was a smuggling hotbed. In the 1780s, the English government burned all the sailing vessels in the town of Deal, located just north of Dover, claiming there wasn’t a single sea-worthy vessel in the harbor that didn’t engage in smuggling.

Once on land, tea and brandy and cigars and the like easily made their way to the markets in London, and the overland smuggling was so elaborate that the English people had no way of knowing whether the tea they purchased had been smuggled in. In fact, some estimate that 75% of the tea in England was smuggled in during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

How did the smugglers operate?

How did the smugglers operate?

Answering this question gets fun and creative and more than a little interesting. The British government did try to prevent smuggling, but keep in mind, the crown needed sailing vessels (most commonly cutters) and sea-worthy men to do this. And while fighting wars with America and France, the crown didn’t exactly have the personnel and vessels to shut down smuggling operations. In fact, it’s often said that the sailors on the kings cutters were people unfit for naval service. There are all kinds of stories of sailors sleeping on duty, and being hired despite old age and missing limbs and a host of other ailments that would make fighting off quick, able-bodied smugglers rather impossible.

The crown did have a preventative service in place, with enough revenue agents that smugglers couldn’t bring a large vessel directly into a harbor and unload illegal goods in broad daylight. Smuggling vessels were often painted black with black sails, making them invisible in the night. Often times smuggling cutters and sloops would drop barrels of brandy into the channel just off the shore, and then “fishermen” would take their smaller crafts out to retrieve the brandy and send it off to London. Sometimes these smuggling cutters would have a rendezvous time and place set up, and the smaller vessels would come and unload the cutter, then return to port under the guise of fishing.

In some towns along the coast, such as Hastings and Dover and the smaller towns in between, the smugglers almost acted like a modern day gang. The smugglers looked out for one another and engaged in illegal activities with each other. Even if the law abiding citizens of the town knew of the smugglers, they’d never turn the smugglers in for fear that their houses would be burned and their families killed.

And yes, sadly, such things did happen.

In other instances, there are stories of smugglers acting out of line and hurting a good, upstanding citizen, after which, the inhabitants of the local village got mad at the injustice and called down the law.

All in all, the topic of smuggling is much too involved to delve into with a single blog post. If you’re interested in further reading on this topic, you could try King’s Cutters and Smugglers: 1700-1855 by E. Keble Chatterton. (The ebook is free.) Or Smuggling in the British Isles by Richard Platt. Platt has a great smuggling website with a lot of information as well.

And you might be interested to know, I’m going to have a rather nefarious French smuggler and his gang play a major role in the sequel to Sanctuary for a Lady. Oh the fun we writers get to have as we explore the dastardly deeds of ages past!

Originally posted 2015-11-08 17:23:09.

written several Regency romances. Her latest series is called London Encounters. Book 2, A Heart’s Rebellion, came out in March. The Rogue’s Redemption, set in both Regency London and frontier Maine, came out in December. She also writes novels set in Victorian England and late 19th century Maine.

written several Regency romances. Her latest series is called London Encounters. Book 2, A Heart’s Rebellion, came out in March. The Rogue’s Redemption, set in both Regency London and frontier Maine, came out in December. She also writes novels set in Victorian England and late 19th century Maine.

anniversary dolls

anniversary dolls

Probably the most infamous of the taxes was the window tax. It was doubly bad because there was also a Glass Excise tax. So you got taxed when you bought the glass for the window and then taxed for having the window.

Probably the most infamous of the taxes was the window tax. It was doubly bad because there was also a Glass Excise tax. So you got taxed when you bought the glass for the window and then taxed for having the window.